Title: Towards an Integral Theory of Creativity

Abstract

Creativity is difficult to define because we keep looking at it like the blind men and the elephant. Behaviorists look at creativity behaviorally, neuroscientists from a brain activity perspective, cognitive theorists from a thinking lens, and so on.

But creativity is all of these and more. It would serve human development and humanity better if we examined creativity through an integral lens. This paper does that using Ken Wilber’s 2006 integral theory model.

Keywords: creativity, integral theory, 4P framework, 5A framework

Creativity by definitions - what's the problem?

First, some background on the tumultuous history of the concept of creativity, as explanation for why attempts at defining creativity has only been recently undertaken.

Up until the Enlightenment, the word “create” and its associated derivatives was used expressly to indicate divine creation (Kaufman & Sternberg, 2010).

The ancient Greeks believed that only nature was perfect, its perfection due to subjugation to natural laws and rules (Tatarkiewicz, 1980). Creativity, on the other hand, implied freedom of action, as the only perfect creator was that which created nature, the Divine. Everything else was designated “art”. The sole exception to this distinction was poetry, as while painters and sculptors merely imitated what they saw, poets saw things differently, as more than just imitation of reality.

The Roman era saw the concept of creativity evolve to include painting and sculpture, believing they also were gifted with divine imagination (Tatarkiewicz, 1980). This was the first time in human history where concepts of imagination and inspiration began to be more broadly applied.

The Christian period further refined the definition of creativity into two concepts: that which referred to God’s act of “creatio ex nihilo “ or creation from nothing, and that which was “facere” or made by man. Art continued to be outside the domain of creativity, in fact also lumping poetry into the craft and thus not creative.

The Renaissance period and its philosophers were the first to describe artists as “thinking up” or “imagining” ideas not represented in nature (Tatarkiewicz, 1980). Painters, poets, musicians, and madmen were all capable of shaping new worlds and new paradises, of producing new songs and inventing rather than imitating.

The philosophical perspective of creativity’s relation to art continued to evolve. By the 18th century, the concept of creativity was being linked to the concept of imagination. There were still objectors, those who argued that imagination didn’t create anything and was only our memory of things, working to combine and manipulate what we already knew.

What broke down the resistance was an increasing realization that, while creativity had historically seemed antithetical to the rules artists employed, in fact rules were a uniquely human invention. By the 19th century, art was not only regarded as creativity, all other preceding concepts of creativity had faded from view. The 20th century saw the expansion of creativity discussion from the arts into science, culminating with an ardent plea by J. P. Guilford in 1950 to the American Psychological Association to close the mammoth gap in researching this increasingly important concept (Guilford, 1950).

It was in this pivotal address that Guilford posed the social basis for his call to action. Industry needed creative people, those who could produce ideas with commercial potential. Branches of government also sought those with inventive potential. Both desired leaders with imagination and vision, i.e. creative leaders. Guilford believed that researching creativity might help identify those creatives in their youth, or develop methods to promote the development of creative personalities (Guilford, 1950).

It was also in this speech and ensuing publication that Guilford set the researchers on a specific path by conflating creativity with creative productivity (Guilford, 1950, p.445). Since 1950, nearly ever paper that reports on creativity findings defines creativity as requiring both originality and effectiveness or usefulness (Runco & Jaeger, 2012). He promoted the idea that creativity can only be manifested in response to a situation or problem, and that the only research worth conducting was creativity related to social and industry problems, as seen in his following lament:

Why is creative productivity a relatively infrequent phenomenon? Of all the people who have lived in historical times, it has been estimated that only about two in a million have become really distinguished (5). Why do so many geniuses spring from parents who are themselves very far from distinguished? Why is there so little apparent correlation between education and creative productiveness? Why do we not produce a larger number of creative geniuses than we do, under supposedly enlightened, modern educational practices? (Guilford, 1950, p.444)

This begs the question, original to whom? Useful to whom? Of course something creative must be original, but does it need to be original in all the history of human ideas, or only to the individual thinking it up? Does it need to be useful to the world at large, or can it simply be useful to the individual as they process the world around them? Guilford’s ask of the 1950s APA audience discounts the idea that someone creating something that existed prior is still exhibiting originality if they had no knowledge of that earlier creation. He similarly dismisses the very subjective construct of “usefulness”, and that creativity can exist in absence of a commercial or social problem.

MODERN CREATIVITY THEORISTS

There has been some shift in the definition of creativity, especially as the topic diverges from purely psychology disciplines towards the inclusion of social scientists and humanities scholars and their relevant specialties. As of the latest version (Runco & Pritzker, 2020), ten categories of creativity theories have been defined, each naturally exploring a different aspect.

Developmental theorists aim both to understand the roots of creativity and the environments in which creativity can flourish (Feldman, 1999). They base much of their work on examining the lives and backgrounds of well-known creative people, attempting to correlate early developmental experiences with later creativity output. They also focus on family structure, as well as longitudinal studies that consider developmental trajectories of cognition, motivation, affect, and personality. (Runco & Pritzker, 2020)

Psychometric theorists focus on the measurement of creativity, distinguishing between creativity and intelligence, the relationship between divergent and convergent thinking with performance and creative output, and creative specific domains (like mathematics or music) versus creativity as a general ability regardless of domain. (Runco & Pritzker, 2020)

Economic creativity theorists draw on economic metaphors. They focus on the market for creativity, and how they provide benefits or impose costs on creators. They describe creativity and creative behaviors in terms of investment, where creators buy low (leveraging unpopular ideas) then sell high (reframing until the idea gains respect). They also explore the market for creative behaviors, arguing that the currency in that market is tolerance.

Creativity stage theorists (as opposed to development stage theorists) focus on defining the stages of creativity (e.g. preparation, incubation, insight, and validation), or by the order of processes (sequential versus recursive.) They emphasize domain-relevant skills, exploring how knowledge of frameworks for generating ideas help to produce unique works.

Cognitive theorists examine the creative process and the creator, emphasizing cognitive mechanisms that result in creative thought. They explore how ideas are combined, whether sequentially or in a remote associative manner. The “geneplore” model of creative thought originates from this group (generate + explore), based on cognitive psychology topics such as conceptual combination/expansion, imagery, and metaphor.

Problem solving and expertise-based theorists also draw from cognitive psychology, and emphasize domain-specific expertise as a critical component to creative achievement. These theorists also study great creators from the perspective of how long they worked in a particular field before devising original contributions, lending support to what is now known as the ‘ten year rule’. (Runco & Pritzker, 2020). These theorists are expressly focused on the type of creativity that leads to paradigm-shifting importance (e.g. invention of the printing press, development of the DNA double helix model, and Darwin’s theory of evolution). The work of these theorists is particularly influential because of direct bearing on Guilford’s plea to research creativity as it relates to useful outcomes.

Problem finding theorists, also highly influential in creativity research, aims to understand how creators come to recognize a problem in the first place, and how they bring their expertise to bear on understanding the nature of the problem. Theorists in this camp focus on understanding the exploratory behavior of creators, especially in the underlying processes like ‘problem construction’ to describe how creators find poorly or undefined problems.

Evolutionary theorists draw their ideas from evolutionary biology, especially using the Darwinian model to argue for a general theory of creativity (Simonton,1999). This model describes how the creative process results from a subconscious generation, elaborations and combination of ideas which are then judged by other people as having merit or not. In this theory of creativity, creators have little control over their own creative process, as it is viewed as a random and chance occurrence of which ideas surface for creation. Creators also have little control over the fate of their work, as it is evaluated by social judgement.

Typological theorists approach understanding creativity by proposing typologies of creators, attempting to explain creativity via the variability in creators rather than the more universalist view undertaken by other theorists. These theorists cast these typologies as a set of categories, some defining them as mutually exclusive, while others as multiple continuous dimensions. Some theorists also attempt to relate these dimensions to each other, offering promise for a multi-level understanding of creativity.

Systems theorists, as one might expect, take the broadest view of creativity, conceptualizing it as a phenomenon of interacting subcomponents converging as complex system. Instead of focusing on what creativity is, they look at where creativity exists, with the predominant interacting components of existing domain knowledge, the individual creator, and the domain’s field of experts. Each element has a role in deciding what counts as creative and worth pursuing.

Yet, even with all these theories, agreeing on a single definition of creativity is still problematic. (Runco & Pritzker, 2020, Runco & Jaeger, 2012) I posit we continue to look at parts of the elephant, instead of the big picture. In the next section of this paper, I propose an alternate approach of mapping each of these theorists’ disciplines into Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory model (2006), defining an Integral Creativity model from which we can then extrapolate new hypotheses about the nature of creativity based on an integral definition.

Frameworks - Integral Theory, 4P and 5A

The AQAL model (standing for "all quadrants, all levels, all lines, all states, and all types") may be the answer to defining creativity by incorporating all the preceding theoretical aspects, as well as additional types and states derived from conceptualizing creativity. Alex and Allyson Grey, of the Integral Institute, made an effort to broach the subject in a brief video (CoSM, 2020), explaining how each quadrant mapped to a creative endeavor.

Briefly, the upper left (UL) quadrant, representing the individual, subjective “I”, is the place where ideas form and the creator’s vision begins. There may be imaginings of what to create, though no action is as yet taken. The upper right (UR) quadrant represents the objective “IT”, the creative product itself. It is the manifestation of the individual’s inner world to the observable outer world. The lower right (LR) quadrant represent the interobjective “ITS” and speaks to creations the creator chooses to share with the collective. Creative products that progress to this quadrant, unless shared unintentionally, were likely created with the express purpose of being shared. Lastly, the lower left (LL) quadrant, the intersubjective “WE”, represents the inner world of the collective, or their response to the shared creative work.

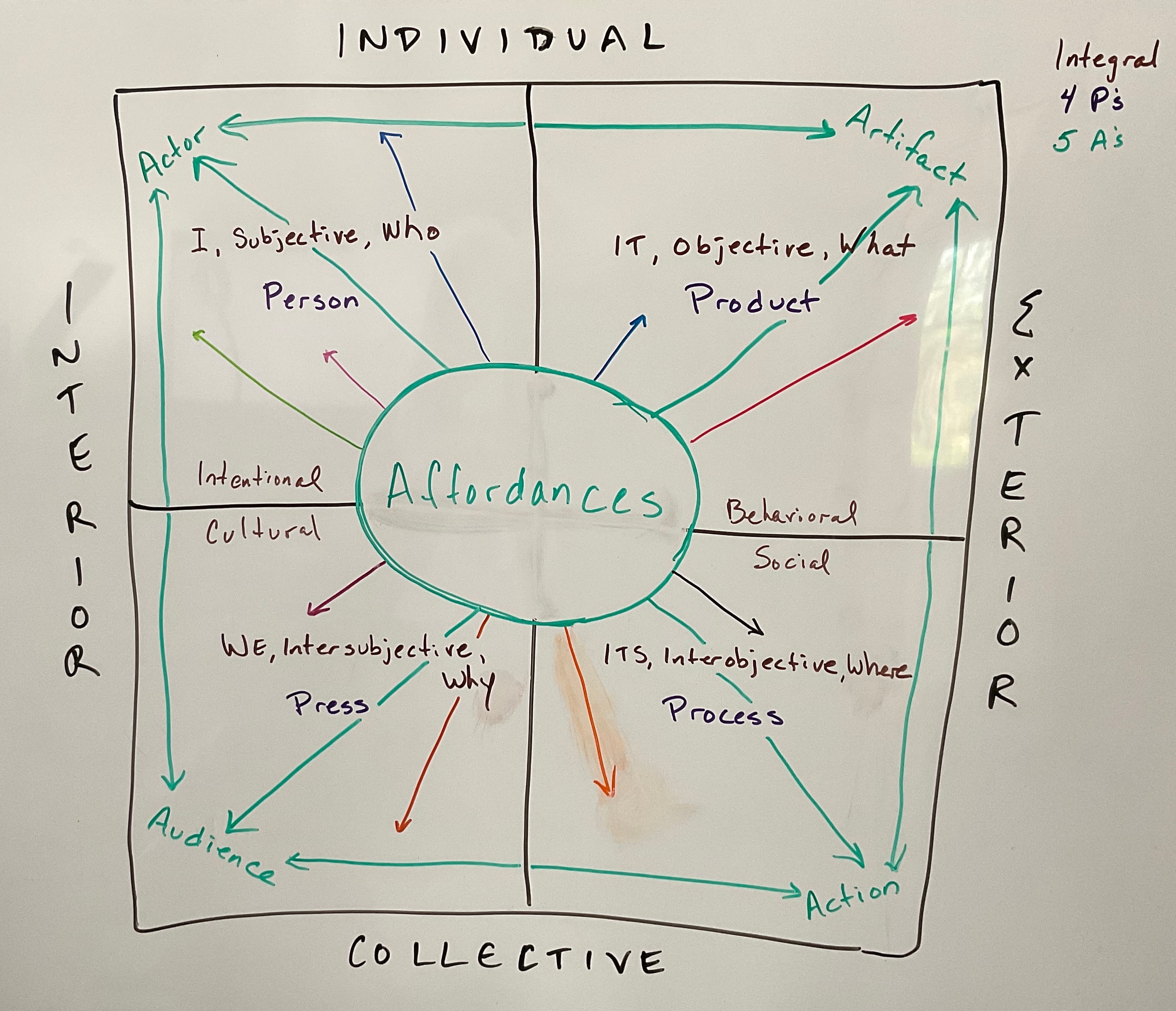

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows the Integral Theory model (in black pen) overlaid with two additional creativity factor frameworks, the “4P” model in purple pen, and the “5A” model in green. For the most part, my interpretation of both creativity factor models seems to fit within the AQAL nomenclature.

The 4P framework of creativity, developed by Mel Rhodes in 1961, describes creativity as four factors working together (Rhodes, 1961):

Person - Rhodes intended this term to cover elements such as intellect, attitudes, personality, physique, self-concept, behavior, and value systems, and to seek correlations between these factors and the predictability of creativity in an individual.

Product - The term specifically refers to the tangible form of an idea, an artifact representing the creator’s thoughts of the time. While this term seems simple, in fact in the context of creativity, it becomes rather complex when married to ideas of originality and usefulness. In Rhodes’ time, there was no clear hierarchy or classification of product to speak of. Today, there is the 4C creativity typology, consisting of mini-c, little-c, pro-c, and Big-C creativity (), but it is still a very loose typology that provides only minimal classification of creative product.

Process - While the term applies to individual factors like motivation, perception, and thinking, it also applies to social factors such as learning, and communicating. In fact, through this lens Rhodes sought answers to whether the processes for creative thinking and problem solving were identical, those problems being of a social nature. He also used this factor to argue that the creative process was itself learnable, teachable, and as much a social construct as an individual one.

Press - This term refers to the relationships between creator and their environment, and how that relationship bears on creativity. The ideas formed in one’s head are in response to the environment in which that person grew up, the memories they retain, and how they perceived that environment. Additionally, this factor emphasizes the effect that the environment has on creativity, especially that of creative amplification by multiple creators. Rhodes (1961) further notes that the great discoveries and inventions throughout time have rarely been the work of a single person, but either an aggregate of others’ lesser inventions or the last step in the progression towards that discovery (Rhodes, 1961).

In a response to the very individualistic and static conceptual schema of the 4P framework, Glaveanu (2013) developed the 5A framework of creative factors. While the 5As themselves are replacements for the 4Ps, the significance of the model is the inclusion of newly defined relationships between poles that describe a spectrum of interaction. The term replacements are fairly straightforward, moving towards a more social conceptualization. What was “Person” and focused only on the individual, became “Actor”, describing not only the Person but also their place as social beings shaped by and acting in accordance to their social context. The former “Product” that only discussed the object itself, became “Artifact” which also included the cultural context in which the object was created, including how others judged it, and why the creator created it. “Action” replaced “Process”, acknowledging both the internal (psychological) and external (behavioral) creative dimensions. “Press” was replaced with “Audience” to articulate the dynamic between the creation and the social world in which it was created. The Audience accounts for the interaction with those assisting in creation, judging significance or worthiness, and using the artifact. Finally, the 5A model added another term, “Affordances”, to delineate the relationship between the material world and resources available towards the creative endeavor.

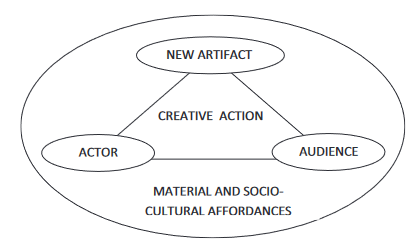

Figure 2 - Integrating the 5As of creativity

Again, the real significance of the 5A framework is that of acknowledging that creativity is a simultaneously psychological., social, and cultural process, and as such, the new relationships defined represent a change to the epistemological position of creativity. Glavenau noted new relationships arising from his model, demonstrating as seen in Figure 2 how the actor exists only in relationship with their audience, actions only take place within a material and social world, and artifacts comprise the traditions and culture of the surrounding community.

Finally, we can see how these frameworks map onto an Integral Theory framework. Referring back to Figure 1, it is clear how Integral Theory quadrants UL, UR, and LL map to the 4P and 5A framework. “Person/Actor” denotes the I/subjective/intentional aspect of the UL quadrant, while “Product/Artifact” maps seamlessly to the IT/objective/behavioral aspect of the UR quadrant. “Press/Audience” can be extrapolated to the WE/intersubjective/cultural nature of the LL quadrant.

I struggled a bit with mapping “Process/Action”. This is the quadrant where the creator interacts with those they wish to share their creation with. My gut says the issue lies in that the creativity models are problem-driven approaches inspired by Guilford’s address in 1950, and that this model may undergo additional revision from my initial conceptualization. In fact, I have already made some modification to the 5A relationships, drawing additional green lines between each corner to indicate relationships between “Actor” and “Action,” and “Artifact” and “Audience”.

What’s next?

Each of the ten theoretical approaches to creativity enumerated early in this paper align to one or more of the 5As and 4Ps. It would not be a difficult stretch to place each on the map of integral creativity proposed here. I anticipate there may be interesting relationships between theories that are not obvious when considering each individually. I also expect that as levels, states, and types are further mapped onto this framework, additional questions and hypotheses may come to light. For instance, while there is substantial empirical evidence of creativity slumps occurring in kindergarten, fourth grade, and again in 7th grade, there is little understanding as to why this occurs. Prevailing hypothesis is that as children develop along cognitive lines and gain formal-operational functions, they abandon creative thought processes in a family environment and educational system that rewards them for rational thought over creative play. (Runco & Pritzker, 2020) I suspect further development of an integral understanding of creativity may help clarify this inverse relationship between human development and creativity.

Conclusion

This paper makes a bold and ambitious claim, that the Integral Theory model can be used to develop a view of Integral Creativity. In pursuit of that claim, the history of creativity and its conceptualizations over time provided the foundation for arguing against a single standard definition. Frameworks currently in use, such as the 4P and 5A models, were explored and then mapped into the AQAL quadrants. The mapping is not perfect, but even so, the exercise highlighted one quadrant that suffers still from the "usefulness" argument of Guilford's 1950 plea for more creativity research. This area is still understudied today, hence why defining creativity still plagues every scholar in this discipline. However, I argue that the issue is not that any of these definitions are inaccurate, but that they are all correct and only need integration to bring us closer to the truth of what creativity actual is.

References

CoSM. (2020, November 24). Ken Wilber’s 4 Quadrants of Creativity with Allyson Grey. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LgxQOqXcR3k

Feldman, D.H., 1999. The development of creativity. In:Sternberg, R. J. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press.

Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5, 444–454.

Kaufman, J. C., & Sternberg, R. J. (2010). The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge University Press.

Rhodes, M. (1961). An Analysis of Creativity. The Phi Delta Kappan, 42(7), 305–310. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20342603

Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.650092

Runco, M. A., & Pritzker, S. R. (2020). Encyclopedia of creativity: 3rd Edition (3rd edition).

Simonton, D.K., 1999. Origins of Genius: Darwinian Perspectives on Creativity. Oxford University Press, New York.

Tatarkiewicz, W. (1980). A History of Six Ideas. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-8805-7